It can be difficult to communicate in print the story of a person who is at heart a filmmaker. Cristian Dimitrius readily admits to film being his primary muse, an inspiration nurtured as a young child in suburban inland Brazil. Fortunately, Dimitrius’ passion extends to images in any medium, so we have still photos to help tell the story.

Growing up three hours from the sea, Dimitrius’ youth may not have been filled with walks along the seashore, but nature in a broader sense was an overwhelming influence. Few of his childhood memories don’t involve nature; this is not to say that mundane small-city life did not influence him, but it served more as confirmation of what he wanted his life not to be.

He joined the Boy Scouts to learn camping and fieldcraft and eschewed traditional sports such as volleyball and soccer for nature sports in school. His sports were mountain biking, rock climbing, hiking and, on those occasions when his family would drive to the coast, snorkeling near-shore reefs and surfing.

His father was president of a local country club that had a large swimming pool and offered scuba instruction to its members. By participating in a self-study program, Dimitrius learned the academics of scuba and did all the training he could handle on his own in the pool. He realized he needed certification to go farther, so he officially took the scuba class.

What started out as a hobby ramped up considerably around the time he joined the Brazilian army. While enrolled in officer’s school Dimitrius had the opportunity to improve his diving skills and taught some basic classes. After moving to the island of Florianopolis to become a biologist, he became a divemaster and an instructor through the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI). His commitment to the scuba lifestyle was now established.

STEPHEN FRINK: I see now how scuba as a recreational sport and profession became an important part of your life, but what motivated you to pick up a camera and become an image-maker?

CRISTIAN DIMITRIUS: I was always inspired by the nature documentaries I saw on TV. What motivated me might have been the films of Jacques Cousteau or Stan Waterman and definitely Howard Hall, but I wasn’t necessarily inspired only by underwater filmmaking. I remember a documentary about big cats in Africa by Dereck Joubert, for example. If it had to do with nature, I was absorbed. I watched these television shows constantly and imagined myself as the storyteller, the one having the adventures.

SF: Did you migrate to filmmaking right away, early in your career, or did you shoot stills first?

CD: I improved my fieldcraft before I moved to filmmaking. My first camera was a Sea and Sea Motor Marine II, which truthfully was pretty limiting, especially compared with the tools I have available to me today. The dive center I was working for had a Hi8 video camera, and they encouraged me to take it out on dives with clients and shoot movies of them as souvenirs. Sometimes I could sell the videos, and I made a little extra money, but more than that I was learning to previsualize, to edit in-camera and imagine what the finished clips might be. Learning to shoot video wasn’t so hard, but learning to edit video was ponderous at the start. So I tried to see it all in my mind’s eye first; this way I could turn around a video faster and not have to work so hard.

We weren’t shooting many videos at that point, so my experience remained pretty basic. I also had a lust for travel. I backpacked because that’s all I could afford, but for a year I traveled along the Brazilian coast. I made it as far as Argentina, where I got a job at a biological research station for a while, and that took me to Antarctica. Summer is the high season for diving in Brazil, and I found I could market my skills as a dive instructor and videographer, at least for those few months every year.

SF: It sounds like an old TV show we had in the U.S., Have Gun — Will Travel. You were the gunslinger for hire, but your video camera was your six-shooter.

CD: Yes, it was exactly like that. After a good season in the North Region or Rio, I would travel to the Caribbean to take it all to the next level, mostly because the diving was so seasonal in Brazil. I landed first in the Dominican Republic and worked there for one year, doing both scuba instruction and videography.

My big break — the one job that most advanced my career — happened when I got a job with Stuart Cove’s Dive Bahamas on the island of New Providence in 2000. There I was a dive instructor, a shark feeder and a boat captain. Eventually I began to work with their photo center; I learned more about cameras and video as a photo pro there than at any other time in my life. It was a time for hard work, and I loved it every aspect of it.

The foundation for my career as a filmmaker today is a reflection of what I learned at Stuart Cove’s. I had to be efficient there. It was very busy all the time, and our guests were sometimes cruise-ship passengers, or maybe they were staying at a hotel on Cable Beach or in Nassau. They would often be there just for the day, and we had to get the videos and stills ready for them to review very quickly or, no matter how inspired and creative the shot, the customer would never see the images.

I had to get it right the first time and deliver the content quickly. But that didn’t mean it had to be boring. In a 30-minute shark dive I would shoot different angles, different cuts. Maybe I’d include some shots from above to establish the scene and to show how many sharks there were, or maybe other angles right at the feeder’s spear would help capture the forced perspective of the bite shot with the customers in the background. The opportunity was there, and I had the will to try to make it different and better on every dive. For me it was a very good education about discipline and the business of filmmaking. I spent three years working with Stuart and Michelle Cove, and I remain grateful for the learning and inspiration they provided.

It was hard work though, often seven days a week. When it was time to move on, I took a sabbatical year to go diving, hiking and rock climbing. My personal batteries needed to be recharged, and I needed the clarity to decide what was next for me.

I was an itinerant cameraman for a while, mostly shooting tourist videos around the various dive hotspots in Mexico. My travels to the Riviera Maya, Holbox, Cozumel, the cenotes and Baja made good content for my blog. People in Brazil started following me every day; this was before Facebook or Instagram. Back then I was shooting a Sony DCR-VX1000 on digital videotapes. It was certainly different technology to capture the action and different tools of sharing, but it still had a viral aspect to it, and I had a pretty vast audience even then. When I was ready to move on to something else, people wanted to send money to keep me on the road. My travels had become a part of their life, a vicarious adventure for them.

SF: How do you manage to integrate your still photography with your filmmaking now?

CD: I was early to embrace hybrid cameras, digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras that could take high-quality stills and also shoot video. In many ways I learned to like those cameras better. They might not have the convenient form factor of a dedicated video camera, but the larger sensors allow me to control the depth of field to my artistic preferences. If I want shallow depth of field in the background to draw the viewer’s eye to some natural behavior from a fish in the foreground, my full-frame DSLR can accomplish that.

Sometimes I prefer to shoot stills rather than video. If I go on a trip by myself, just for fun, I tend to shoot almost all stills. The postproduction workload is less, and I still have the joy of creation. Pictures are great for sharing on social media, or I could potentially use them for a future book or to promote a film. These days when I am hired to do a job it is usually as a filmmaker, but I always try to find time for some stills.

The tools I travel with depend on the kind of assignment I have. For serious broadcast television work I’ll pack my RED digital cinema camera and my Canon EOS 5D Mark III. Fortunately, the same Canon lenses work on both cameras; my favorites include the 8-15mm fisheye zoom, the 16-35mm II wide-angle zoom, a 12-22mm Tokina and the 100mm macro, often with a Nauticam Super Macro Converter. I have Nauticam housings for both cameras, and I use Inon Z-240 strobes for stills and Keldan Luna 8 lights when shooting video. Like almost any working pro these days, I also travel with several GoPro systems because they are so awesome for the point-of-view action I like to shoot.

SF: While I had known of your work, the first time we spent on the road together was during your assignment to document the Bahamas Underwater Photo Week (see “A Week Underwater in the Bahamas”). I was impressed with your dedication to your craft, for you were never without a camera in your hand. I can’t imagine how many digital gigabytes you shot that week, as video represents huge chunks of data to manage and archive. Yet you found time to post to social media every day — not just a casual photograph but often an edited video. To me that says your postproduction skills must be impressive.

CD: It is true that I have had to become an efficient editor in the field, or I could never do what I am tasked to do for clients. Often I am traveling alone, without an assistant or an editor or a soundman. I go to remote places, and getting myself there is hard enough. A large team would be expensive and often intrusive for the intimate behaviors I am trying to film about some shy marine animal or even a dangerous predator. I can manage myself, but a larger crew might actually get in the way.

To prepare me for what I currently do, I got a job with a production company in Sao Paulo. I started out as an assistant cameraman and then was promoted to cameraman, editor and finally producer. In less than a year of on-the-job training I learned how to make a TV show.

What was most immediately obvious was that I needed to know more about topside filming, because underwater shots alone weren’t going to cut it for the network. I’m now happy and comfortable shooting above and below the surface. I film only nature though. I don’t do fashion, products, news or events. To keep me engaged, my work has to be about the natural world.

Having a background in biology has been helpful, because I know when I am seeing unique behaviors; however, just as when I was a Boy Scout, fieldcraft is very important. I need to know how to spend time in the field without suffering. An underwater photographer will never achieve excellence without being a good diver first, and a nature cinematographer requires field skills to flourish, or sometimes even to survive, on some of these assignments.

SF: Who are your primary clients these days? It seems you’ve come a long way from shooting souvenir videos of scuba divers.

CD: In Brazil I stay very busy with National Geographic, Discovery Communications and the BBC. If they have projects happening anywhere in Brazil, I’m likely to get a call. I also shoot a lot for our Brazilian dive magazine, Mergulho. I recently had the opportunity to work on an IMAX project in the Bahamas as well, shooting 6K video.

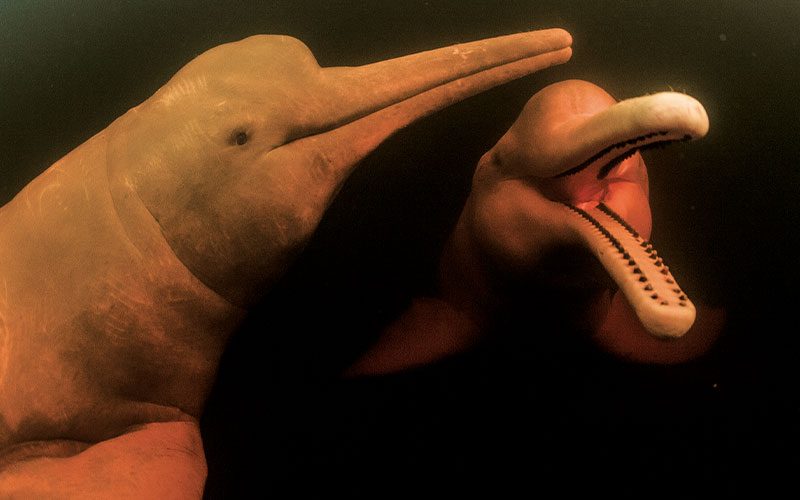

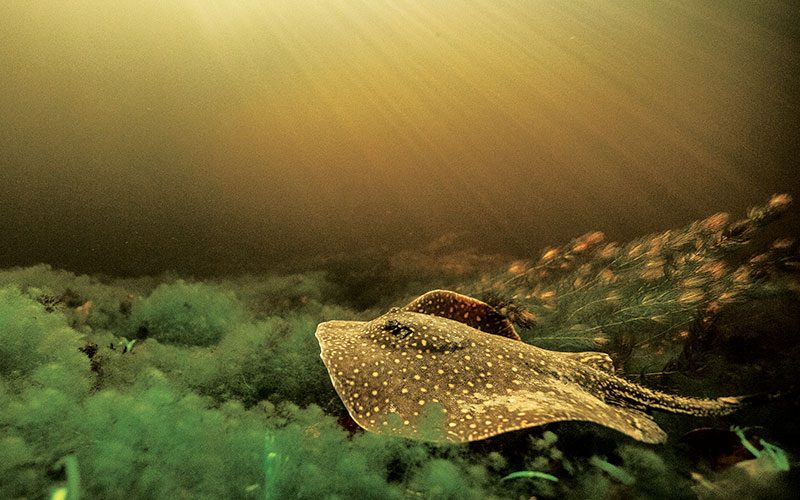

The one project that keeps me most occupied is our television show, which airs to 50 million viewers each Sunday. I am the researcher, shooter and presenter on an adventure segment. We specialize in different locales; lately it has been the Bahamas, U.S., Norway, Africa, etc. I tell about 15 stories each year — it could be about polar bears, elephant seals, lampreys or even mayflies. As long as it is a strong story, one that is compelling for our audience, I’ll go anywhere on the planet to shoot it. My main goal is filming, of course, but I shoot stills on location as well and one day soon will do a book about my adventures.

If I may leave your readers with one final thought about my work, please understand it is all about cultivating a passion for nature. I want my viewers to fall in love with the planet. All nature photographers and filmmakers need to have a conservation mindset they carry through to their work, for unless we protect what we love we’ll be out of a job and, more important, out of a place to live on this earth.

The things I do with sharks or tigers or crocodiles is not to prove I am brave but to show we can all share the same planet and coexist in peace.

SF: Are you on the road as much as it seems? Whenever I see one of your Facebook or Instagram posts, you are in some distant and very remote place.

CD: I’m on the road about 70 percent of the time at the moment, which is a lot, but I’m well adapted to this lifestyle. My wife works with me and supports my travels, which is extremely important. I know that right now is the time for me to do what I do. I’m 39 years old and recognize that I won’t do this forever, but for now I have momentum and I like this crazy existence. Next week I go way south to Patagonia and then way north to the Artic. Life is too short to be bored.

Explore More

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2014