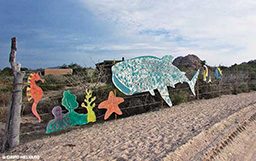

At the end of a six-mile dirt track in lower Baja on the sun-dappled Sea of Cortez, a hand-painted cutout of a whale shark hangs on a cattle fence near a welcome sign for Cabo Pulmo. The sign reads “Santuario de mar, tierra y gente — Sanctuary of sea, earth and people,” a low-key introduction to one of the world’s most productive marine parks.

In the waters just off the small desert village of some 200 locals and owners of solar-powered second homes, you can find mobs of sea lions, swarms of yellow- and bluestriped grunts with big, luminescent golden groupers swimming through their ranks along with huge turquoise, blue, green and orange parrotfish, tiger and bull sharks, shoals of bigeye silver jacks and squadrons of leaping mobula rays that — photographed airborne against the sere desert hills — have become the symbol of Cabo Pulmo’s 28-square-mile national marine park. In different seasons the park also attracts whale sharks, humpback whales and nesting sea turtles.

Although the water temperature was cool and the visibility little better than 20 feet during the oven-baked July days when I did my back rolls off small, beach-launched panga dive boats, it felt great to drop into the salty wilderness amid an abundance of frisky fish and healthy corals. There were spur-and-groove canyons full of fan, cup and stony corals, green moray eels and garden eels that swayed like prairie grass on the sandy flats. A big 8-foot stingray lay half buried in the sand, while porcupine pufferfish and yellow-tailed gray sturgeon grazed the corals. Humphead parrotfish chewed coral and pooted sand, a major source of replenishment for those tropical white-sand beaches we all like to visit. There were Moorish idols, stately queen angels and curious 10-pound snappers, including cuberas that would quickly be caught and eaten anywhere else along the rugged 800-mile-long desert peninsula. Baja, the original California, has long been a place of challenge and adventure, tranquility and hope for visitors and settlers alike.

In 1940 John Steinbeck and Monterey marine biologist Ed Ricketts (Doc in Cannery Row) sailed through these waters on an expedition later recorded in Steinbeck’s book The Log from the Sea of Cortez. Sitting on the deck of their chartered fishing boat, the Western Flyer, taking notes below circling pelicans and frigates whose descendants still work the area, Steinbeck described the microorganisms of the Cabo Pulmo reef: “Clinging to the coral, growing on it, burrowing into it, was a teeming fauna. Every piece of the soft material broken off skittered and pulsed with life — little crabs and worms and snails. One small piece of coral might conceal 30 or 40 species, and the colors on the reef were electric.”

The story of how the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park later came into being is almost as inspiring as its still-teeming waters. “My grandfather came here and began freediving for pearls when it was a fishing camp,” said Judith Castro, a respected local leader with dark hair and a broad, friendly face, and chair of the board of directors of Amigos para la Conservación de Cabo Pulmo (ACCP), translated as Friends for the Conservation of Cabo Pulmo. “Soon it became famous for its quality pearls. He was the first pearl diver; he built a ranch with cows and sheep, and he raised corn and vegetables. He and his sons then became commercial fishermen — there were about 10 houses by then.”

Her eyes sparkled as she recalled growing up with her father, Enrique, and brothers Mario, Paco, Kiki and Milo in the sagebrush and saguaro-cactus fishing community with its empty azure sky and star-spangled nights. But soon, as in much of Baja and the world, the sea bass, snapper and cubera were overfished and depleted, and the fishermen’s livelihoods were threatened. “As a teen I’d watch them go out fishing before sunup and come back near dark without any fish; that was super sad for me, and they were losing money because of the cost of ice and gas.” Soon the men had to spend part of the year away from home, fishing the Pacific for shrimp and lobster.

“Then in the 1980s, Autonomous University of Baja California Sur scientists came to study the coral reef (the only one in the Sea of Cortez) and talked to my father, uncle and brothers and let them know about the importance of the reef and gave them dive masks to see it for themselves. From there it took 10 years to decide to protect it.”

Castro’s brother Mario became a leader in making that decision, talking to others in the community and appealing to the government to create the no-take reserve. He’s a short, burly and somewhat taciturn man with dark hair, a mustache, flip-flops, swim trunks and a tee. “I was the first one from here certified [as a scuba diver] in 1991,” he said outside the small office at Cabo Pulmo Sport Center (also known as Cabo Pulmo Divers), the original of three dive shops now operating in town. “It’s the only one still run by Mexicans,” half-grouses his wiry son, David, as he strips off his wetsuit after leading a dive, exposing his shoulder tats of a manta ray and other marine life.

“On June 6, 1995, the government created it [the marine park] and said no fishing, and for the first years after that it was too hard,” Mario recalled. “We’d have one, two, three people a week coming to see it. But now we have a bunch [of divers, kayakers and ecotourists]. I taught David and my other boys to dive, and we make a better living than before.” He shows me a picture of his 8-year-old grandson, David’s boy Jeshua, wearing a cowboy hat and vest. “Now we teach him to dive,” he said, his dour face lighting up with a grin.

Across the open beachfront from the dive shop is the ACCP’s two-story cinderblock office, its entry decorated by children’s paintings of sea life. Established in 2003 by Judith, Mario and Canadian activist Dawn Pier to protect the local sea turtle population, the environmental group soon expanded its aim to include protection of the marine park and community. Today Guatemalan biologist and diver Paulina Godoy heads the organization’s small staff. The day I visited, Paulina was feeding her 4-month-old baby Maya while her 4-year-old son Orion and Judith’s 5-year-old Yerick scampered between the office and tree-shaded yard, oblivious of the 95-degree heat. From 2009 to 2012 ACCP fought a protracted battle against a planned Spanish megaresort just up the road that was to include 27,000 hotel and condo units and that could have destroyed the reef with sediment runoff and other polluntants. With support from other Mexican and international environmental groups, they won their battle when former President Felipe Calderon cancelled the resort’s permits in June 2012.

Still, other developments are being planned for the relatively isolated East Cape area between the city of La Paz and the sprawling tourist nexus of Cabo San Lucas with its shopping malls, high-rise hotels and sportfishing marinas. Recognizing that some development is inevitable, ACCP is working on a strategic plan with other cape communities and urban planners for a sustainable future. Their vision and goals include providing fresh water, sanitation and other public services for Cabo Pulmo, creating an urban plan in keeping with their existing low-impact way of life and promoting ecotourism that provides locally based jobs. They also want to strengthen protection for the marine park, recognizing that good stewardship is key to their future.

Ecotourism dollars already have helped open a learning center for the town’s kids. A big wall mural shows three mermaid girls studying while a sea turtle brings them more books on its back. On my visit I saw an older American couple rehearsing a group of 18 youngsters for a “symphony” performance of a cappella voices and percussion instruments.

Globally, no-take marine protected areas (MPAs) such as Cabo Pulmo — particularly those created from bottom-up seaweed groups (marine grassroots) of fishermen and community activists — have proven the resiliency and popularity of ocean restoration. After all, it’s doesn’t take a rocket scientist to understand that if you stop killing fish they tend to grow back. A study by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography found the Cabo Pulmo reserve has been especially resilient, showing an astonishing 463 percent increase in its biomass (more and bigger fish) between 1999 and 2009. Yet, despite new and expanded marine wilderness parks — what ocean explorer Sylvia Earle calls “Hope Spots” (see the Spring 2013 issue of Alert Diver) — in the Western Pacific, California and Costa Rica, and campaigns to protect both Arctic and Antarctic waters, almost 2 percent of the world’s ocean area today is protected from fishing, drilling and dumping. Scientists have suggested that to provide a biological reserve for the future of our blue planet we should protect 20 percent of the ocean.

On my last dive at Cabo Pulmo, David Castro leads a father-son team and me to the wreck of an old tuna boat, 50 feet down. Sunk during a storm in 1939, the pilothouse and hull have become abstract structures covered in corals, green anemones and a few dazzling nudibranchs along with the usual litter of grunts, snapper and jacks. We swim away onto the sand flats, where David spots three big bull sharks. One, about 8 feet long with the girth of a fighter jet’s fuel tank, swims in and out of view, cruising past me with little apparent interest in a bipedal bubble blower. A few minutes later I spot another big fella — or maybe it’s the same one; it’s hard to tell in the limited visibility.

If someone were to ask why we were swimming through murky waters looking for big sharks, I’d say it was for the same reason you hope to see a grizzly bear when you visit Alaska: One, they’re magnificent animals, totally adapted to their environment, and two, to paraphrase author and naturalist Ed Abbey, “If there’s not something bigger and meaner than you out there it’s not really wilderness.” While we’ve learned how badly we can trash our ocean planet, it’s good to be reminded we can also restore it. Cabo Pulmo’s once overfished and depleted waters today are a wilderness and a wonder.

David Helvarg is an author and executive director of Blue Frontier, a marine conservation group. His new book is The Golden Shore: California’s Love Affair with the Sea.

© Alert Diver — Q1 Winter 2014