Czech police divers train others to save lives.

The wars in the former Yugoslavia ended many years ago, but the consequences of the conflicts remain, with an alarming number of mines still scattered throughout the country. The resulting death toll is rising despite the efforts of authorities, nongovernmental organizations and individuals, who combined to successfully destroy 168,000 mines in 2018. Despite the mine clearance work that has been underway since 2011, the number of victims in 2016 was close to 2,500.

Capt. Jiří Šejba is a police diver and a member of the Department of Special Diving Activities and Training (DSDAT) based in Brno, Czech Republic, and the Directorate of the Riot Police Service for the Police Presidium of the Czech Republic. In this interview he discusses the biggest pitfalls of each mission, the current state of training and when the area could be safe again.

As the number of landmine victims worldwide continues to grow, what is your view of the situation in the Balkans where you actively operate?

The DSDAT focuses its work underwater, but most of the mined area is on dry land. The Bosnian team is trying to deal with the situation in their way, and it’s not our place to comment. Moreover, we don’t have relevant data from the locals to accomplish further research, which would be necessary for making any conclusions.

We always go for two weeks to do what we agreed to do, and then we leave, and the Bosnians remain. They seem happy and appreciative of our help. We feel good about the work, because we believe that every explosive found and destroyed saves a human life.

During the past seven years, how many mine-clearing missions have your police divers and explosives technicians completed in the waters of the Sava, Una and Drina rivers in Bosnia and Herzegovina? Have you planned other operations?

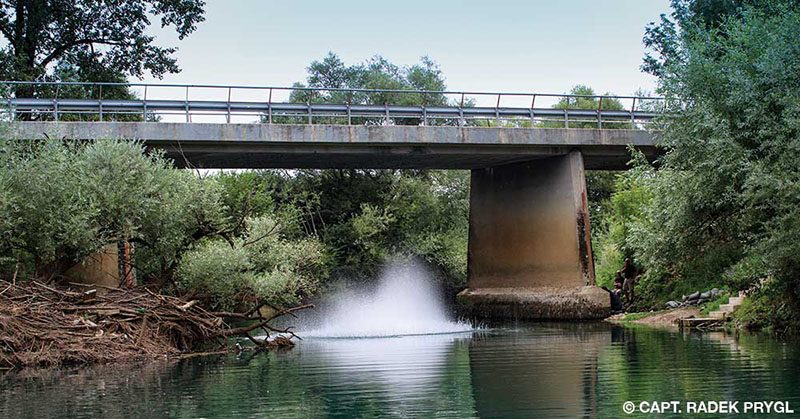

We have completed 15 mine-clearing operations with the DSDAT team since our first contract operation in 2011. We were in the Orašje area in 2012 and later in Novi Grad and the Sava River. We completed three mine-clearing missions in 2016 in Brčko, the Sava River, Bihač and Una River. The following year we continued at the Sava River, overlapping into the Drina River and the towns of Bosanski Brod and Goražde. In 2018 we worked mainly at Lake Kop close to the town of Šićki Brod near Tuzla. We have planned more operations.

Can you estimate in terms of months, years or decades when the Balkan region could be safe again?

The Bosnia and Herzegovina government plans on completing the mine clearance work by 2030, but experts say that may extend to 2040 due to the intensity of the work. But the fact is it isn’t easy to estimate. There’s always a surprise — other discoveries, new locations, poorly accessible terrain and lack of people or financial resources.

Czech police divers started to train units in the Republic of Serbia. Do you also train other units?

Czech police divers from DSDAT have been training explosives technicians of Bosnia and Herzegovina in dive activities since they began to do clearance in their country. We trained the State Investigation and Protection Agency (the state police of Bosnia and Herzegovina) unit in 2012 and 2013. During that time we also organized training the Special Anti-terrorist Unit from Montenegro. From 2014 until now, the Federal Department of Civilian Protection unit in Bosnia and Herzegovina has been undergoing training.

What are the biggest pitfalls for the divers from the Serbian unit?

It’s the same everywhere, whether they are Bosnian or Serbian divers or anyone elsewhere in the world. Some divers have more sensitivity and talent for underwater work, while others have less and therefore need longer to adapt. Unless there are health or psychological problems that would make diving impossible, we can teach all members to perform these activities. The skills of the divers we have trained are good examples of how we can develop anyone with the willingness to do this kind of work.

What are the technical demands?

Preparation for the training includes ensuring that the necessary equipment is available and ready, securing the lecturers and training site, and coordinating all logistics. Each piece of equipment must be tested, fully functional and appropriately certified.

The divers start their training with theoretical lessons and then gradually move into the underwater environment. The training program gradually adds more and more knowledge about the use of specialized equipment and various search methods, which everyone must master perfectly. We want them to eventually be completely independent and able to safely carry out their activities without us. Even the most sophisticated technique still cannot replace the human hands and brain.

All explosives technicians must be confident in their diving so they can concentrate fully on the destruction of the explosive material. Diving itself becomes mere transport to the workplace; it’s the same for all working divers around the world.

Where does the training take place?

We try to organize training in locations where it’s possible to efficiently supervise the trainees and where they feel mentally comfortable, which is usually by the Adriatic Sea. We have conducted training in Montenegro at the Bay of Kotor, in Croatia on Vis Island and near the city of Šibenik, and in Neum, Bosnia and Herzegovina. One training session took place in Salzkammergut, Austria, at Lake Attersee.

What devices do you use?

For dive training, we initially use the same basic dive equipment that amateur sport divers use. It’s necessary for trainees to first learn the basics of diving and develop from there to achieve perfect control of the equipment. After this phase, we add specialized equipment such as full-face masks with communications, Kirby Morgan helmets, metal detectors or lift bags. Members of DSDAT also use Liberty closed-circuit rebreathers and specialized equipment, including underwater sonar systems and the remotely operated vehicles.

Training also includes a surface team to take care of the divers. This team must be able to operate all the technology so that the diver’s experience underwater is secure, and they can concentrate purely on their task. The team must be able to control surface communication stations, know various means of signaling technology and work with ropes, sonar and robots. Vessel management is another necessary and essential skill. The divers alternate working above and below the surface and must learn the necessary skills for both teams.

What do you value most about these devices?

All these devices, with the proper knowledge of their operation, make our activities much easier and faster. They reduce manual labor and save precious time. You should note, however, that a necessary condition of using the devices is also their subsequent care and maintenance, which you should not neglect.

How long does it take to clear mines from a riverbed? It must be very slow and demanding work.

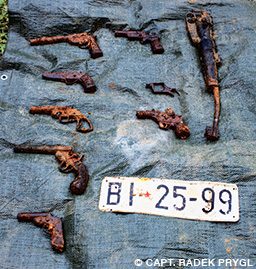

This question is complicated. When you say “mine clearance,” people usually imagine the action of searching for and disposing of landmines buried in the ground. But this term includes all activities that we use to seek and dispose of the explosive material. Nobody plants classical mines underwater except for large naval mines designed to destroy ships.

Underwater we see mainly unused ammunition or ammunition that was fired but failed. There is a big difference between these two types of ammunition. Unused ammunition, with a few exceptions, does not threaten an explosion. Fired ammunition — which can include various types of artillery mines and grenades, hand grenades or even bombs — is dangerous to handle because it is unpredictable. In these cases, we usually prefer to dispose of it on the spot underwater.

The terrain of the riverbed — soft, muddy or formed by hard deposits — will affect the search. We start by using a metal detector to reveal areas that we need to search next. Sometimes we may spend a lot of time and effort to dig more than 1.5 feet (0.5 meters) to find the metal object. After all that digging we could find that it’s only a nail, for example, and then we have to start the search again.

We use our hands or a hoe to clear the riverbed. We occasionally need to use a hose to move away pieces or rely on suction from a water dredge to clear space to work. The divers decide on the methods and tools based on a risk assessment and the type of ammunition found. It can take from five minutes to more than an hour to clear about 10 square feet (1 square meter). It is slow and often painstaking work, but we know that we are saving lives by doing it.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2020